| Nature | News Feature Sharing - [url=]

[/url] [/url] -

- [url=]

[/url] [/url]

Cocktails for cancer with a measure of immunotherapy The next frontier in cancer immunotherapy lies in combining it with other treatments. Scientists are trying to get the mix just right.

13 April 2016

Article tools

Margaret Oechsli Some cancer drugs (pictured here, dried adriamycin viewed under a microscope) might work better when paired with immunotherapies.

In cancer research, no success is more revered than the huge reduction in deaths from childhood leukaemia. From the 1960s to the 2000s, researchers boosted the number of children who survived acute lymphoblastic leukaemia from roughly 1 in 10 to around 9 in 10.

What is sometimes overlooked, however, is that these dramatic gains against the most common form of childhood cancer were made not through the invention of new drugs or technologies, but rather through a reassessment of the tools in hand: a dogged analysis of the relative gains from different medicines and careful strategizing over how best to apply them side by side as combination therapies.

Cancer-fighting viruses win approval

“It wasn't just about pounding drugs together,” says Jedd Wolchok, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “It was about understanding the mechanism and figuring out what should be given when.”

That lesson has particular relevance in cancer research today. A new class of immunotherapies — which turn the body's immune system against cancerous cells — is elevating hopes about combination therapies again. The drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, have already generated great excitement in medicine when applied on their own. Now there are scores of trials mixing these immune-boosting drugs with one another, with radiation, with chemotherapies, with cancer-fighting viruses, with cell treatments and more. “The field is exploding,” says Crystal Mackall, who leads the paediatric cancer immunotherapy programme at Stanford University in California.

Fast-moving trends in cancer biology often fail to meet expectations, and little is yet known about how these drugs work together. Some observers warn that the combinations being tested are simply marriages of convenience — making use of readily available compounds or capitalizing on business alliances. “In many cases, we're moving forward without a rationale,” says Alfred Zippelius, an oncologist at the University of Basel in Switzerland. “I suspect we'll see some disappointment in the next few years with respect to immunotherapy.”

But many clinicians argue that delay is not an option as their patients queue up for the next available clinical trial. “Right now I have more patients that could benefit from combinations than there are combinations being tested,” says Antoni Ribas, an oncologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “We're always waiting on the next slot.”

Lying in wait Immunotherapies have been more than a century in the making, starting when physicians first noticed mysterious remissions in a few people with cancer who contracted a bacterial infection. The observations led to a hypothesis: perhaps the immune system is able to kill tumours when made hypervigilant by an infection. The concept has vast appeal. What better way to beat a fast-evolving biological system such as a tumour than with a fast-evolving biological immune system? But it took decades for researchers to turn that observation into something useful.

Immune cells boost cancer survival from months to years

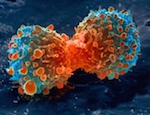

Part of the trouble, they eventually learned, is that tumours suppress the immune response. T cells, the immune system's weapon of choice against cancer, would sometimes gather at the edge of a tumour and then just stop.

It turned out that a class of molecules called inhibitory checkpoint proteins was holding those T cells at bay. These proteins normally protect the human body from unwarranted attack and autoimmunity, but they were also limiting the immune system's ability to detect and fight tumours.

In 1996, immunologist James Allison, now at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, showed that switching off a checkpoint protein called CTLA-4 helped mice to fend off tumours1. The discovery suggested that there was a way to re-mobilize T cells and beat cancer.

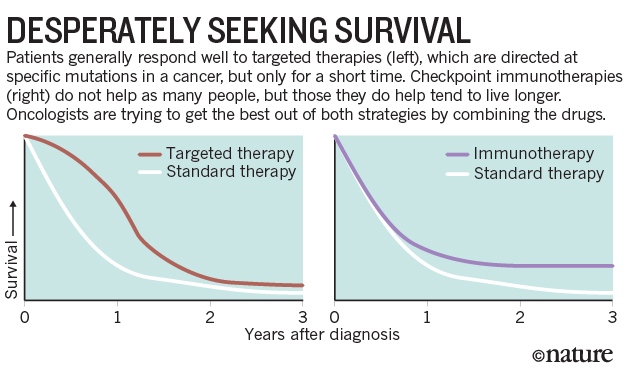

In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first checkpoint inhibitor — a drug, called ipilimumab, that inhibits CTLA-4 — to treat advanced melanoma. The improvements were modest: about 20% of patients benefited from ipilimumab, and the survival gain was less than four months on average2. But a handful of recipients are still alive a decade after starting the therapy — a stark contrast with most new cancer drugs, which often benefit more patients in the short term, but don't have a durable response (see 'Desperately seeking survival').

Ipilimumab was at the leading edge of a flood of checkpoint inhibitors to enter clinical trials. The drug's developer, Bristol-Myers Squibb of New York, followed up with the approval of nivolumab, which inhibits the protein PD-1. And a host of other companies have jumped into the immunotherapy fray, as have academics such as Edward Garon at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Our group gladly shifted into this,” says Garon, who began focusing on checkpoint inhibitors in 2012. “It was very clear this was going to have a major impact.”

But even as the family of checkpoint inhibitors was rapidly expanding, the drugs were running up against the same frustrating wall: only a minority of patients experienced long-lasting remission. And some cancers — such as prostate and pancreatic — responded poorly, if at all, to the drugs.

Therapeutic cancer vaccine survives biotech bust

Further research revealed a possible explanation: many people who were not responding well to the drugs were starting the treatment without that phalanx of T cells waiting at the margins of their tumours. (In the lingo of the field, their tumours were not inflamed.) Researchers reasoned that if they could raise this T-cell response first, and recruit the cells to the edges of the tumour, they might get a better result with the checkpoint inhibitors.

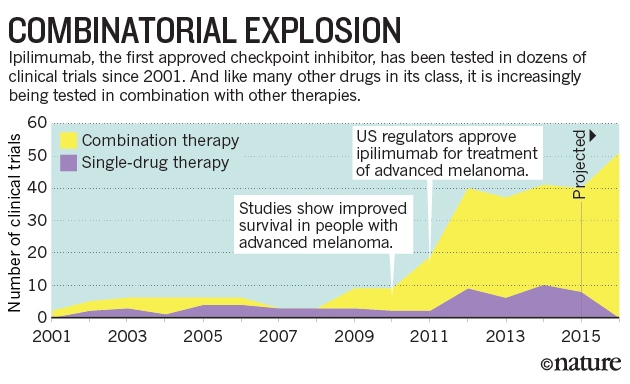

That realization fuelled a rush to test combinations of drugs (see 'Combinatorial explosion'). Radiation and some chemotherapies kill enough tumour cells to release proteins that the immune system might then recognize as foreign and attack. Vaccines containing these proteins, called antigens, could have a similar effect. “On some level, one can make an argument for almost any drug combining well with an immunotherapy,” says Garon. “And obviously we know not all of them will.”

Mixing it up One of the first combinations to be tested was made up of two immunotherapies — ipilimumab and nivolumab — at once. Although the targets of these drugs both do the same job, silencing T cells, they do so in different ways: CTLA-4 prevents the activation of T cells; PD-1 blocks the cells once they have infiltrated the tumour and its environment. And treating mice with compounds that block both proteins yielded a more-inflamed tumour as well3. “There was reason to think that if you block both, the T cells will be even more ready to kill the tumours,” says Michael Postow, an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

Together, ipilimumab and nivolumab boost response rates in people with advanced melanoma from 19% with just ipilimumab to 58% with the combination4. The combination also produces more-dangerous side effects than using either drug alone, but physicians are learning how to treat immunotherapy reactions, says Postow.

Source: clinicaltrials.gov

Ipilimumab generally doesn't help people with lung cancer when given on its own, but researchers are now testing it with nivolumab. Normally, they would not have bothered to investigate a combination involving a drug that had failed on its own, Garon says.

The new approach is grounded in immunology, but some researchers worry that the effort could be wasted, he adds. Researchers are also testing inhibitors of other checkpoint proteins, including TIM-3 and LAG-3, in combination with those that block PD-1.

Cancer treatment: The killer within

The combination approach is breathing life into drugs that had been shelved. For example, a protein called CD40 stimulates immune responses and has shown promise against cancer in animals. But in the wake of disappointing early clinical trials, some companies put their CD40 drugs to the side.

Years later, mouse studies showed that combining CD40 drugs with a checkpoint inhibitor could boost their effect. Now, at least seven companies are developing them. Cancer immunologists have listed the protein as one of the targets they are most interested in studying, says Mac Cheever, a cancer immunologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

Cancer vaccines — long pursued by researchers but burdened by repeated failures in clinical trials — may also see a renaissance. There are now more than two dozen trials of cancer vaccines that make use of a checkpoint inhibitor.

Some promising combinations have been uncovered by serendipitous clinical observations. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, were conducting trials of epigenetic drugs, which alter the chemical tags on chromosomes. They shifted a handful of people with lung cancer who had not responded to the drugs to a clinical trial of nivolumab. Five of them responded — a much higher proportion than expected. The discovery became the seed for an ongoing clinical trial launched in 2013 to study combinations of epigenetic drugs and immunotherapies. Preclinical work has now provided evidence that epigenetic drugs can affect aspects of the immune response.

Riding the wave These chance observations could lead to real advances, says Wolchok. “We're riding the wave of enthusiasm.” But extracting the most from these combinations will require more well-designed preclinical studies to support the human ones. Just as attention to combinations of chemotherapies fuelled advances in treating paediatric leukaemias, the current combinatorial craze will require careful planning to work out the right pairings and timing of therapies.

Personalized cocktails vanquish resistant cancers

Another class of drug, known as targeted therapies, could also receive a significant boost from immunotherapy. These drugs, which target proteins bearing specific mutations, generate a high response rate when given to patients with those mutations, but the tumours often develop resistance to the drugs and come roaring back. Coupling targeted therapies with a checkpoint inhibitor, researchers reason, could yield both high response rates and durable remissions.

One of the first targeted therapies for melanoma was an inhibitor that is specific to certain mutations in BRAF proteins that can drive tumour growth. However, an early attempt to combine this drug with ipilimumab was aborted when trial participants showed signs of possible liver damage5. No one was injured, but for some it was an important reminder that combinations can yield unanticipated side effects. “It was a good lesson for us to learn,” says Wolchok. “It will not be as simple as we imagined.”

Paying careful attention to sample collection during clinical trials would help researchers to catch toxicity problems early, says Jennifer Wargo, a cancer researcher at MD Anderson. “We're making mistakes by looking just at clinical endpoints,” she adds. “We need to be smarter about how we run these trials.”

In one of his latest trials, Wolchok wants to combine immunotherapy with a drug that targets a cellular pathway that some cancer cells use to maintain their rapid division. Cancers with mutations in this pathway, which is regulated by the protein MEK, can be extraordinarily difficult to treat.

Cancer therapy: an evolved approach

But the pathway is also important for T-cell development, so Wolchok is working to determine the right timing for the treatment. One approach could be to use a MEK inhibitor to quiet tumours in mice and to release tumour antigens. He would then wait for the T-cell response to rejuvenate before adding the immunotherapy. “You want to make sure you're not trying to activate the immune system at the same time you're turning off that signalling,” he says.

Garon is watching such trials with optimism, but he's aware that there may be a limit to how well combinations will perform. He sees a cautionary tale in a drug from an earlier era that works mainly in people with a mutation in the protein EGFR. Researchers spent a decade trying to find drugs that could turn a non-responding patient into a responder. “It is now clear that there probably is no such agent,” he says. “I'm hopeful we won't be repeating that same response, but we have to watch our data cautiously.”

Data frenzy Researchers are so ravenous for those data that the results are being unveiled at major meetings at an earlier stage than in the past, he adds. “People are getting up and presenting response rates when the number treated is five,” Garon says. “We generally have had a higher threshold than that.” He worries that presenting such early data could prompt community physicians in the audience to start making decisions on treatments before they are appropriately studied.

The excitement is also fuelling a frenzy of clinical trials that are often based on speed rather than rationale. “Right now I'm kidding myself if I say I'm picking a combination because I have a scientific reason to pick it,” says Mackall. “It's likely to just be what was available.”

Cancer: The Ras renaissance

The strategy may still produce some wins. “There is plenty of opportunity for serendipity now,” says Robert Vonderheide, who studies CD40 at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But as the field matures, he says, this could give way to a more-systematic approach, similar to the careful planning and testing of variables used for paediatric leukaemias.

Despite his concerns, Garon is excited to be a part of the immunotherapy wave. Last autumn, he and his colleagues held a banquet for the patients who had been enrolled in his first immunotherapy trials three years earlier. These were the lucky survivors — the few who had shown a dramatic response. As he looked around the table at the guests of honour, he marvelled at their recovery. All had been diagnosed with advanced lung cancer, and many had been too weak to work. Now they were talking about their families, re-embarking on careers and taking up old hobbies such as golf and running. “We've never been able to hold a banquet like that before,” he says. “I would love to hold many more.”

Nature532,162–164(14 April 2016)doi:10.1038/532162a |